"There is nothing more abominable than that trash which is circulated under the name of Ignatius."

– John Calvin, Institutes of the Reformer of Geneva.

Ignatius and Polycarp are pressed into service by today's Christian apologists as witnesses to many outrageous claims – not least the silly notion that "The disciples died for their conviction that Jesus rose from the dead."

The two saints supposedly wrote their testimony before themselves going on to particularly splendid martyrdoms.

Ignatius' "witness" to apostolic sacrifice is this single reference found in the epistle to the Smyrnaeans:

"They touched Him and believed, for they had had contact with the flesh-and-blood reality of Him. For this cause they despised death and were found its conquerors."

Lust for martyrdom

Ignatius wanted to die. He feared the "jealousy of Satan" might rob him of his "prize".

In barely 1800 words of Ign. Romans he appealled no fewer than 14 times to his co-religionists NOT to intercede to save his life.

"I am God's wheat ... ground fine by the lions' teeth to become the purest bread for Christ."

"I am yearning for death with the passion of a lover."

"I am truly in earnest about dying for God."

Kinda gives you a warm feeling, huh?

"Hated by the World"

Another gem from Ignatius which should stiffen the resolve of any potential suicide bomber:

"Christianity is a thing of might when it is hated by the world."

– Ignatius, Epistle to the Romans, 3.

Why was Ignatius not executed at Antioch?

One of the four great cities of the Roman Empire Antioch had its own fine amphitheatre. The emperor himself was in residence prior to his campaign in Armenia and Parthia.

Antioch amphitheatre (mosaic, Museum of Antioch)

Where DID they get their ideas?

Is it just another coincidence that the city that requested "a complete set" of Ignatian letters (Philippi) itself stood on the great eastern Roman highway – the via Ignatius (aka Egnatia)?

The Birth and Death of the Saviour was a SECRET?!

A STAR revealed ALL!

"Mary's virginity was hidden from the prince of this world, so was her child-bearing, and so was the death of the Lord.

All these three trumpet-tongued secrets were brought to pass in the deep silence of God.

How then were they made known to the world?

Up in heavens a star gleamed out, more brilliant than all the rest; no words could describe its lustre, and the strangeness of it left men bewildered."

– Ign. Ephesians 18.

Justin on Ignatius

Justin Priscus (the so-called "martyr"), writing in the mid-2nd century has not a word to say about any imperious bishop of Antioch.

A long-term resident of Ephesus, Justin records nothing of Polycarp either. Neither the celebrity martyrdoms of the dynamic duo, nor the compendium of their letters, merits a comment.

Could it be that none of the Catholic fable had been invented in Justin's day?

Origen on Ignatius

2nd/3rd century Origen has little enough to say about Ignatius.

"Indeed, I remember that one of the saints, by name Ignatius, said of Christ: 'My Love is crucified.' and I do not consider him worthy of censure on this account."

– Origen of Alexandria, Prologue, Commentary on Song of Songs.

The quotation appears to be from Ign. Romans, 7. but at least one scholar/ translator (John Parker) argued that the whole passage was written and inserted into the text by Dionysius the Areopagite!

WOW! The pious imagination goes into overdrive

"On December 20 in the year 107, Ignatius was escorted from the Roman galley that had taken nine years to deliver its prisoner from Antioch to Rome and was brought to the Flavian Amphitheater, the Coliseum, where at the conclusion of the Roman festival he was fed to the lions."

"When Domitian persecuted the Church, St. Ignatius obtained peace for his own flock by fasting and prayer. In the year 107, Trajan came to Antioch, and forced the Christians to choose between apostasy and death. He was devoured by lions in the Roman amphitheatre. After the martyr's death, several Christians saw him in vision standing before Christ, and interceding for them."– Lives of the Saints

|

Like the twin stars Castor and Pollux, two martyred saints shine brightly in the firmament of the early Christian dreamscape – Ignatius Theophorus ("God bearer") and Polycarp ("Many fruits"). Purportedly, one was bishop of Antioch, the centre of Christianity in Roman Syria. The other bishop of Smyrna, the centre of Christianity in Roman Asia. Together they span the void that exists between a Palestinian pageant set in the mid-years of the 1st century and the reality of a Church fabricating a noble history a century and a half later. Each luminary lived to a great age after a forty-year episcopate characterized by absolutely nothing worthy of a comment in any religious or secular history. At the close of their purported lives each made a highly symbolic journey to Rome, the prelude to a glorious and theatrical martyrdom that would echo down the ages. Neither was an original mind, able to expatiate on "Christology" or the Divine Will. On the contrary, both were – surprisingly – dogmatic "Catholics" in an age when the future orthodoxy was indiscernible within a panoply of contending sun-god cults. These heroes of the faith exist solely through fake "letters" and bogus martyrologies, the former prosaic and devoid of any memorable sentiment, the latter utterly fantastic and unworldly.

Star witness In today's world of Christian apologetics the phantom saint Ignatius heads the list of "witnesses to witnesses":

"Having seen the risen Jesus they were so encouraged that they despised death", quotes Habermas approvingly from the epistle of Ignatius to the Smyrnians. Yet at best, Ignatius can only be a witness to the belief of others – there is no suggestion that he ever saw an apostle die. The one apostle he might conceivably have met, John, supposedly died of old age! But what if Ignatius-cum-Polycarp is a demonstrable fabrication, the work of 2nd century Catholic Orthodoxy, seeding its own beliefs

into an earlier era as "evidence" for a rebuttal to the challenge of Gnosticism, what then of this "witness to Jesus"?

The God bearer – Ignatius "Theophorus"

The "life" of Ignatius presents us with a remarkable paradox: the eminence of an unknown bishop. Only an alleged martyrdom and a collection of letters purportedly written on his final journey lifts "Ignatius" from the void. Even his martyrdom, in fact, is never detailed but only anticipated. The letters of Ignatius, however, were faithfully preserved – an oddity in itself if they really belong to a time of apocalyptic anticipation and the world "passing away". From them the early church constructed the martyr's "final journey" and added a glorious finale in the Colosseum at Rome. More importantly, the epistles of Ignatius stand as crucial witness to the claims of the Catholic Church to an apostolic foundation and a purity of its faith. After apparently some forty years of pastoral service, with not a whisper of episcopal preeminence, Ignatius blazed into glory, casting his radiance across the eastern Roman empire. Remarkably, in the interlude between condemnation and execution, Ignatius was able to set down for posterity all the essential dogmas of Catholicism. Indeed, at a time when the epistles of Paul were "unknown" it seems a collection of Ignatian letters was a prized possession (Polycarp to the Philippians, 13), even before the bishop "won" his cherished martyr's crown. Curiously, the "persecution" that sealed Ignatius' fate elicits scarcely a word from the martyr-elect. Ad nauseam he speaks of his impending execution as a "reward", a "prize" a "great joy". He says nothing of other members of his Antiochian church (did no one else suffer?) or of the circumstances of his trial. The primary target in every letter (with the exception of Romans) is heresy – which clearly suggests composition at a time, not of persecution, but of fierce doctrinal challenge.

The character that emerges from these "final letters" is an unconvincing brew of towering humility and diffidence laced with imperious intolerance and bombast. Ignatius, describing himself as the "last and least" of the Syrian church (Trallians 13, Smyrnians 11), "fears" he may not be worthy of martyrdom. Yet he speaks with the "voice of God" (Philadelphians 7) and only his status as a "condemned prisoner" prevents him "using the peremptory tone of an Apostle" ! (Trallians 3) Although Ignatius avers his "inferiority" to the congregations to whom he writes he cannot resist boasting of a superior "ability to comprehend celestial secrets and angelic hierarchies, the disposition of the heavenly powers, and much else both seen and unseen" (Trallians 5). He describes even his chains as "lordly fetters"! (Smyrnians 11). But what do we really know about Ignatius? Secular history is silent. Surprise, surprise.

The fable examined According to church "tradition" Ignatius was the child picked up by Jesus noted in Mark 9.36 ("And he took a child and set him in the midst of them.") Supposedly, Ignatius became bishop of Antioch about the year 69 – the year of Polycarp's birth. Yet it is Polycarp, forty years Ignatius' junior, who is said to have been a disciple of "John the Apostle". Then again, in some versions of the yarn, both Ignatius and Polycarp are said to have been taught by the apostles, "fellow students", even though one was already a bishop when the other was still a child! Uncertainty surrounds the ordination of Ignatius as bishop of Antioch. Eusebius manages to maintain that Ignatius was second in succession to both Euodius (HE 3.22) and Peter (HE 3.36). One tradition has it that Peter ordained Ignatius. However, the Apostolic Constitutions, dreamed up in the late 4th century (a collection of rules and doctrines purportedly handed down by the twelve apostles to the nascent church), in Book 7.4, maintains rather that Paul ordained Ignatius. If true, this would remove the blessed apostle of Tarsus from the clutches of Nero and martyrdom in Rome – and create a mystery as to why Paul says nothing of his star acolyte. The highly localized "persecution" which determined Ignatius' fate is quite unknown to secular history and Trajan, the purported "persecutor", was a benign and tolerant ruler, despite the best efforts by Christians to rubbish his reputation. Indeed, certain of Ignatius' own comments could undermine the claim that there had been a persecution at all. Arguably, a sectarian rift has been healed:

But in any event, even the journey to martyrdom is woefully incomplete. We learn nothing of the excursion until the entourage is already in the heart of Asia Minor and nothing at all of events in Rome where Ignatius is said to have met his fate. It is, almost certainly, because of the inadequacies of the original Ignatian yarn that the Church felt impelled to augment it with another. A twin star circles in orbit about Ignatius, a bishop named Polycarp, no great letter writer but a martyr's martyr, who makes his exit with superlative humility and a heroic forbearance ... well, to die for.

Amazing journey

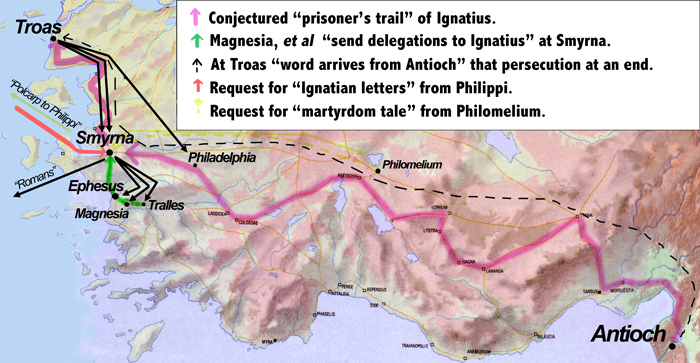

Anomalies of the Ignatian Grand Tour The route that Ignatius might have taken from Antioch to Troas in the far west of Roman Asia is entirely conjecture. It is generally thought to have been overland although the imaginative 10th century "Martyrdom of Ignatius" records a sea voyage: "he came down from Antioch to Seleucia, from which place he set sail". But then this late and fraudulent testimony also reports verbatim the conversation that the saint supposedly had with emperor Trajan! Well of course, in fiction, you can write what you like. Awkwardly, Ignatius himself writes of his visit to Philadelphia, ninety miles from the sea, and of being hurried along by his military escort from city to city. But far from hurrying, the Ignatian entourage evidently moved at a ponderous pace, allowing a surprising number of convenient encounters and reunions along the way. Was there a fast-track, one wonders, for Christian emissaries, allowing them to outpace the imperial train – or were Ignatius and his entourage sauntering along like retired tourists?

All this on the supposition that the prison train would dally all the while at Smyrna and that the delegates would gain access to the prisoner when they arrived! Yet the captive bishop refers to his military trustees in the harshest terms:

• At Troas, the story repeats itself with only slight changes. Ignatius, now attended by Burrhus, a deacon from Ephesus, "received word" from distant Antioch. Apparently, "Philo, a deacon of Cilicia" and "Rheus Agathopous, one of the elect" had been in hot pursuit of the official party all the way from Syria. They brought the good news that the persecution had abated and that "peace had been restored" to the church. The chronology is baffling. How long did the prison detail mark time at Troas? Evidently, it was the churches of western Asia Minor – learning of the "persecution" long before they encountered Ignatius himself – that had, through prayer, been instrumental in bringing the persecution to a close:

The "good news from Antioch" is an element of pure theatre, setting up the next stage of the improbable tale. Bizarrely, by the time that Ignatius writes to the Philadelphians the messengers have joined the bishop in "preaching God's word" – surely a liberty beyond all reason for a prisoner condemned for his proselytizing? The news brought no reprieve for the would-be martyr and yet Ignatius was so elated he called on the churches of western Asia Minor to send delegates to Antioch to "congratulate" the brethren on their new found "peace". Given the expense and dangers of such long distant travel, what purpose did this serve? The only victim was Ignatius, still alive but under sentence of death. How could a celebration be in order when the martyrdom – the crux of the whole story – had yet to occur? It was, apparently, the "Divine will" (not a Roman officer) that urged Ignatius across the Aegean and onto Neapolis and his eventual fate. Ludicrously, the captive bishop urges Polycarp "to write ahead to the churches along the route." If the imminent martyrdom of Ignatius merited such attention it certainly demonstrated how exceptional was such an event.

The martyrdom of Ignatius – getting better with every re-telling

As it happens, at the time when Ignatius may have taken his final bow the emperor was preoccupied with a major campaign against Parthia which taxed the resources even of the Roman state. At such a time, why would the emperor eschew the perfectly serviceable local arena for Ignatius's execution and instead, assign a troop of ten guards to traipse their captive the long way round the eastern empire and back to Rome? In fact, Trajan's legate, Hadrian, had been holding court at Antioch, perhaps from as early as 113, marshalling and supplying the army with which the emperor would careen through Armenia and Mesopotamia. Was the imperial court really the least bit concerned with a marginal sect of religious innovators? In his History of the Church, Eusebius introduces Ignatius in book 3.36, saying he became "well-known" at the time Polycarp was bishop in Smyrna and Papias bishop in Hierapolis. Of his martyrdom Eusebius has but a single sentence:

All part of the fun ...

Part 2: The Ignatian Epistles – a compendium of fraud

Sources:

'Save' a friend e-mail this page

Copyright © 2009

by Kenneth Humphreys.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||