Discuss the world's favourite imaginary friend on the JNE YouTube channel

Godman to the Max

More powerful than Zeus; more radiant than the Unconquerable Sun.

A mother more pure than Artemis, more virginal than Vesta; a human AND a heavenly Father.

At his birth the credulous shepherds of Adonis AND the adoring priests of Mithras – the Magi.

About his head, the nimbus of Mithras. Healing powers more wondrous than Asclepius, wine-making skills superior to Dionysius. A better shepherd than Apollo; a brighter Light of the World than Horus.

A brotherly love more sublime than Buddha's.

In life more humble than the lowliest slave, more majestic than the noblest king.

In death, suffering more agony than the suffering servant of Isaiah, yet more glorious than any conqueror's triumph.

Roll up, roll up ... the God with Everything.

No One Home

"Roman control of Judaea was first established by Gnaeus Pompey.

As victor he claimed the right to enter the Temple, and this incident gave rise to the common impression that it contained no representation of the deity - the sanctuary was empty and the Holy of Holies untenanted."

– Tacitus, The Histories, 5.9.

A Judge of All Humanity

18 psalms, written during the last days of the Hasmoneans (but ascribed to "Solomon") pass judgement on Pompey and Aristobulus and anticipate a messianic deliverer.

"When the sinner waxed proud, with a battering-ram he cast down fortified walls,

And Thou didst not restrain. Alien nations ascended Thine altar, They trampled proudly with their sandals..

Bless God ..

He will distinguish between the righteous and the sinner, And recompense the sinners for ever according to their deeds;

And have mercy on the righteous, delivering him from the affliction of the sinner..

And now behold, ye princes of the earth, the judgement of the Lord .. judging all that is under heaven. "

– Psalms of Solomon, 2

Warning! Don't Step on the Grass

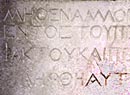

Inscription from Herod's Temple.

The punishment for sneaking a peek at Jews at prayer was a tad severe:

"No foreigner is to enter within the balustrade and embankment around the sanctuary.

Whoever is caught will have himself to blame for his death which follows."

Messiahs R'Us:

"Lowly Servant Raised to King"

With the death of Herod the Great in 4 BC, one of his slaves, "Simon of Peraea", put a diadem on his head and declared himself king.

He launched himself into a career of arson and plunder, setting fire to the royal palace at Jericho and several other royal residences.

The commander of Herod's guard caught and beheaded him.

"Shepherd King at Emmaus"

In the same year "Athronges, the shepherd", with a diadem on his head, was also hailed as king. At the head of four brothers and a large band of adventurers he murdered and pillaged the region near Emmaus.

– Josephus, Antiquities 17

The Roman governor of Syria, Quinctilius Varus, used three of his four Syrian legions to suppress the rebellions of Simon and Athronges.

"Jesus World" – The Divided Inheritance of Herod's offspring

In the early empire the masters of Rome favoured client kings who kept their thrones by compliant behaviour and regular remittance of taxation.

– Palestine, first decade of 1st century AD. Salome got her property after the fall of Archelaus. Lucky girl.

Many currents fed the Jesus myth, like streams and tributaries joining to form a major river. In order to compete with rival gods Jesus had to match them point for point, miracle for miracle. Jesus the Christ, King of Kings, Light of the World, High Priest forever, Good Shepherd, Judge of the quick and the dead, and the Saviour of Mankind is nothing less than – nothing other than – an omnibus edition of all that had gone before, the final product of ancient religious syncretism. In essence Jesus Christ is like every other ancient god, a personification of Principals and Forces. More than anything else, the figure of Jesus symbolized and personified Just Law, Divine Punishment and Reward. The myth did not require the happenstance of a genuine human life to get it going – which is one reason why, as a human being, the superhero is at best only partially formed, even after passing through several revisions and re-workings. Every miracle, every pronouncement and every micro-drama of the godman's supposed ministry can be shown to be a midrashic creation, teased out of Jewish scripture and a handful of supplementary sources. Not a scrap of an authentic human story is to be found. And why would there be? Jesus the man did not exist. He is a collective work of fiction and the culmination of two centuries of pious aspirations.

Civil Wars I – "Judgement Day" With the death of Alexander Jannaeus (103-76 BC), the first Maccabee to openly take the title king, a bitter conflict arose between his two sons John Hyrcanus II and Judas Aristobulus II. John sought help from an Arab chieftain of Idumea named Antipater, head of the Herodian family. Both claimants to the Hasmonean throne appealed to Rome and in 63 BC the Romans arrived and resolved matters by by imposing a mosaic of client kingdoms and self-governing cities in the region (Philistia, Phoenicia, Israel, Judah, etc.). Pompey, having captured Jerusalem and strolled around the inner sanctum of the Temple – he famously remarked "It was empty" – gave the High Priesthood to Hyrcanus. Thus ended a century of Jewish independence. In Pompey's Roman triumph of 61 BC, Aristobulus was compelled to march in front of the conqueror's chariot in chains. Five years later the captive prince escaped his Roman prison and fled to Judea, only to be recaptured and returned to Rome. His erratic fortunes turned again when Julius Caesar found a role for him in his campaign against Pompey, at that time ensconced in Syria. But the hapless Aristobulus was poisoned on the journey east. Pharisees recorded with satisfaction the "divine punishment' dished out to Aristobulus in the so-called Psalms of Solomon. Disillusioned with Jewish kings yet again (for the Maccabees had begun by restoring "righteousness") the Pharisees shifted the focus of their hope to a messianic deliverer, more priestly than kingly, who would judge sinners and reward the righteous. The proclaimer of God's dawning kingdom was now identified with the image of an apocalyptic judge.

Civil War II – An Apocalyptic Age Twenty years later, the victor of Rome's own civil war, Caesar, also chose to support Hyrcanus but appointed the Arab Antipater as epitropos ('regent'). This left out in the cold a dissatisfied claimant to the Jewish throne Antigonus, second son of Aristobulus II. He appealed to the other power player in the region, Parthia, promising the Parthian king ‘500 wives of his enemies’ for his intervention. A Parthian invasion followed, triggering renewed civil war among the Jews in which Hyrcanus was taken prisoner (40 BC). Antipater's son Herod (the 33-year-old governor of Galilee) rescued him, but Hyrcanus was a spent force. Herod, on the other hand, had already made a name for himself by executing ‘bandits’ (Galilean nationalists led by Ezekias) who had been causing trouble on the borders of Roman Syria. His renewed loyalty to Rome would assure his future. But in the short term the situation looked bleak. Parthia rapidly occupied most of Judaea and installed Antigonus as king in Jerusalem. Herod's Roman patron, Mark Antony, ruler of the eastern provinces, was at this time dallying in Egypt with Cleopatra, a monarch with her own imperial designs on Palestine. Herod fled to to Rome and appealled directly to Octavian, himself now locked in rivalry with Antony. With the Senate's blessing, Herod was made King of the Jews and after a 3 year campaign at the head of two Roman legions, he was finally able to enter his capital. But the situation remained volatile.

The Romans Execute a 'King of the Jews' Now there's an idea ... Antony's own ambitions required heavy taxation of Judaea and this exacerbated hatred towards Rome and Herod himself. Antigonus languished in Herod's gaol but worryingly he retained both popular and religious support. There was an obvious solution: his execution.

The dishonourable death of a Jewish king at the hands of Rome would shortly be overshadowed by the Battle of Actium and the downfall of Antony himself. Herod, the consummate political survivor, promptly ingratiated himself into the train of Octavian and went on to rule his turbulent realm for another quarter of a century. With a tally of ten wives and at least 15 children he developed a healthy phobia that his throne might be usurped from within his own extensive family (though it's rather unlikely he worried about a carpenter's son). With

their hopes of deliverance from iniquity dashed more thoroughly

than ever before – an upstart, sacrilegious Arab as king and rapacious Roman overlords

– the cohorts of piety turned with delirium to dreams of a ‘Messiah’,

an End-time

figure who would arrive to judge the world.

The Rise and Fall of the House of Herod "We want a Davidic King"

Herod himself eventually won the support of a majority of the Sadducees, partly by the creation of an Herodian aristocracy of his own placemen and partly by rebuilding the rather lacklustre Temple built by Zerubabel. This so-called "Second Temple" had been desecrated by Antiochus in 168 BC and had been "re-dedicated" by Judas Maccabeaus a few years later. Herod's design for the Temple exceeded the dimensions of the fabled 'Temple of Solomon' found only within the pages of the Book of Chronicles. Most of the grandiose construction was completed between 20-10 BC, though work continued on peripheral areas almost up until its destruction nearly a century later. The massive project was not equalled in the city for more than a thousand years. It was the most impressive abattoir ever built. Even so, Herod won few friends among the pious, who were delighted by his death in 4 BC. The Pharisees – loosely divided into two factions, the "liberal" house of the rabbinic sage Hillel (30 BC -10 AD) and the harsher, more conservative house of Shammai – remained hostile to the Herodian princes who inherited their father's realm. The territories allotted to the "tetrarchs" ("rulers") – Panias and Batanaea, ruled by Philip until his death in 34 AD; Galilee and Peraea, under Antipas until his exile in 39 AD – passed to Herod's grandson Agrippa I (son of the executed Aristobulus). Astute like his grandfather, Agrippa remained on good terms with both Caligula and Claudius. As a loyal Hellenistic client-ruler he was rewarded with further territory and the restored title of "King of the Jews". He died suddenly in 44 AD. But the territories that passed to Herod's senior son Archelaus as "ethnarch" ("prince") – Judaea, Samaria and Idumea– were more problematic. For a decade Archelaus confronted continuous internal dissent and a frustrated Emperor Augustus deposed him in 6 AD. His territories were reorganised into a minor Roman province with a permanent Roman garrison in Jerusalem and a military "prefecture" installed in Caesarea. The first Prefect, Coponius, under instructions from the Governor of Syria, Quirinius (in Greek "Cyrenius"), began by conducting a tax census. Archelaus, a Romanised youth, was given the short straw – the Jewish heartland, suffering heavy unemployment with the end of Herod's ambitious public works program. He fell from favour after heavy-handed treatment meted out to the Jewish aristocracy and a series of rebels and "messiahs". His brother Antipas was more fortunate, ruling Galilee for more than 40 years. Astute and capable – despite the infamy for beheading John the Baptist – Antipas won the backing of Emperor Tiberius. Even the author of Luke is generous towards Antipas, introducing a third "trial" for JC not found in Matthew:

The more capricious Caligula exiled Antipas to Gaul.

Pressure Cooker of Dissent Throughout the 1st century of the common era, while the Herodian aristocracy happily danced to the tune of the caesars, the exploitation of the common people intensified. Upon their backs now weighed the priesthood, the landowning elite and the Romans. The stage was set in which rabbis, radicals and rebels would appeal to the despised and neglected masses. On offer was a hero of the people.

Sources:

'Save' a friend e-mail this page

Copyright © 2005

by Kenneth Humphreys.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||