"The Jews... embraced every opportunity of overreaching the idolaters in trade."

– Edward Gibbon (Decline & Fall of the Roman Empire)

Graven Images R Us!

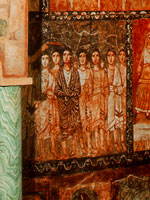

In the 2nd and 3rd centuries, in defiance of both Law and tradition, synagogues were decorated with human figures.

The deluxe decor of the synagogue at Dura-Europa on the upper Euphrates (3rd century AD).

Along with the Patriarchs is a rendering of Pharaoh's naked daughter!

Dura-Europa was originally a Greek colony on the Euphrates. In 165 AD it became a Roman garrison city.

On the frontier of two empires and the major trade route between Palmyra and Mesopotamia, Dura became a wealthy caravan terminus and centre of pan-Jewish commerce. It was destroyed by the Sassanids in 256 AD.

Soon-to-be-king David stands out from the crowd in his purple toga (just like the Caesars!)

"Pagan?

We have pagan ..."

4th century synagogue near Tiberias.

Mosaics of Greco-Roman nude athletes, the sun-god Helios and signs of the zodiac decorate the floor!

4th century sarcophagus.

The Jewish menorah, this time with personifications of the Seasons and cherubs. (Catacomb Vigna Randanini, Rome)

Something for the Boys ...

14th century Hebrew manuscript "Golden Haggadah" ("Stories of the Exodus").

Pharaoh's naked daughter takes a dip (a popular theme). For personal use.

|

The Way of the Rabbi Whatever daughter religions might spin off from old Judaism, the parent religion itself had inevitably to refashion itself for the new era. After the disaster of 135 AD, a number of Jews retreated into asceticism, banning meat and wine altogether, since sacrifice in the temple was no longer possible. Others lost themselves in mysticism, attempting to reach the "celestial throne" via their imagination (the apostle Paul would have understood!) – the forerunners of the later "Kabala". But for all

their suffering, most Jews were not ready to bastardise their

traditional creed by infusing it with the dying godman mythology.

The vacuum was filled by"Rabbinic Judaism", the

inheritor of the Pharisee tradition.

The Rabbis

became "clericalised" –

obsessed with cultic rules as a practical substitute

for the lost temple. They peopled the air itself with beneficent

and malign spirits. A Jewish "code to live by" - the Mitzvoth (the

forerunner of monastic rules) detailed no fewer

than 613 rules, governing every pious moment from waking to sleeping,

to keep the Jew on the right side of an all-seeing God.

But the new Judaism also had its factions and with the 4th century triumph of Judaism's most wayward heresy – Christianity – the momentum within the empire for conversion to Judaism ceased. Indeed, "adoption of Jewish manners" became an illegal activity and, faced with official hostility, many descendents of the original pagan converts found it prudent to embrace the now favoured Christianity. In regions beyond the reach of Rome, Jewish proselytizing continued. Iranians of Adiabene, Ethiopic tribes of the Horn of Africa, and Arab tribes of the Yemen and Spasinou/Charax were among those pagans who found an enthusiasm for the religion of Abraham and Moses. Subsequently, even greater numbers from the Turkic tribes of the Caucasus and Berber tribes of north Africa also embraced the Mosaic faith. From India to Spain, from Arabia to Gaul, the Jewish "people" – bonded by a faith not chromosomes – capitalising upon a network of safe havens, and a filial presence in every major resource, from African ivory to Germanic slaves, to throw themselves into the commerce of the ancient world. Jewish merchants traversed with impunity the hostile frontiers between Rome and Persia, sailed the sea lanes from the chilly rivers of Germany to the balmy seas off the Horn of Africa. The Jews became dealers in amber and fur, gold and silver, slave-traders and money-lenders. But they were also dealers in superstition as well as produce:

In the mid-years of the second century, the centre of commercial/religious Judaism lay on an axis between Palestine and Babylon. The light hand of Rome allowed the displaced Jews of Siria Palestinia to re-establish their ancestral faith, complete with religious police and a self-appointed hierarchy, with a new corporate headquarters at Tiberias, in Galilee. At its head stood a "CEO" in the guise of an hereditary Patriarch of the West, the recipient of tithes which had once gone to the Temple. Every synagogue was visited by legates of the Patriarch – they were called ‘Apostles’! – who collected contributions. As a high dignitary of the Empire, the Illustrious Patriarch shared the status and privileges enjoyed by Rome's consuls, top military commanders and chief ministers. One provincial governor of Palestine learned the hard way the folly of insulting the Patriarch, who out-ranked him in the official hierarchy. He was executed by the ferocious Christian Emperor Theodosius I. Lamented the Christian writer Origen:

During the reign of the Emperor Antoninus Pius (138-161), and under a wary Roman eye, Jewish schools of the Law were allowed to re-open. The Jewish scribes began codifying God’s ineffable word at the very time Christian scribes were furiously at work writing and revising their own holy stories. Across the Persian (Parthian) frontier, another hierarch, the so-called Prince of the Captivity, had also furnished himself with a fabulously appointed ecclesiastic court, financed by the Jews of Persia. Here in Parthia, prestigious centres of Judaism flourished:

The five year war ended in a painful triumph for Rome. Returning troops were to bring plague into the heart of the Empire and in the long term, the withdrawal of legions to fight in the east was to fatally weaken the Danubian front. But, with the capture of Ctesiphon, once again Mesopotamian Jews were brought under the dominion of Rome. Unfortunately for them, they threw in their lot with a rebellious Roman commander, Avidius Cassius, which set the normally tolerant Marcus Aurelius against them. As a result of a power struggle between the two pontiffs in the 3rd century – very reminiscent of the conflict between Rome and Constantinople – the Babylonian Jews became subordinate to the Western patriarch (business merger?) Pagan Rome, wearied by recurring rebellions of the Jews, came to regard them with suspicion and disdain– but the Christian Empire which was to follow refined this contempt into a bloody hatred. Though tolerated for their commercial usefulness the Jews would ever-after face the murderous intent of those who were "Loving Servants of the Lord."

Sources:

Copyright © 2004

by Kenneth Humphreys.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||