Discuss the world's favourite imaginary friend on the JNE YouTube channel

An empire of religious syncretism, 4th-1st centuries BC.

While Rome waged a struggle with Carthage, the Ptolemies were masters of the eastern Mediterranean.

For 300 years Greek-Egyptians ruled an empire of religious syncretism, a period in which notions of a superhero godman gestated, subsequently to be historicized by the Christians.

Horus – An original Light of the World

''Early Mystery-Religion was syncretistic… The Persian Mithra-cult was at least partially egyptianized; the Egyptian Isiac cult largely Hellenized.'

– S. Angus, The Mystery Religions, p20.

"Jewish" horned altar – for the god Serapis!

Greek island of Delos, centre of the Ionian Confederacy, 3rd century BC.

And for the god Yahweh?

"And Adonijah feared because of Solomon, and arose, and went, and caught hold on the horns of the altar."

– 1 Kings 1.50.

Syncretic overload –

A god with everything

Tyche (Fortuna) – traditionally wears a mural crown – representing the walls of the city guided by the goddess. But here she also wears the headdress of Isis, complete with her crescent moon.

In her left arm she holds the horn of plenty (symbol of a bountiful harvest) and in her right hand she holds a rudder (guiding fortune and dominion over the sea),

She also wears the wings of Nike (Victoria), the goddess of victory, and the deerskin of Dionysus (Bacchus), the god of wine.

Around her right arm coils a serpent, an attribute of the goddess Hygieia (Salus), one of the daughters of the healing god Aesclepius.

Just how much more holy can a girl get?

(Early Imperial period. Staatliche Museen, Berlin)

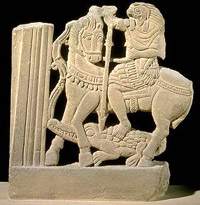

Horus becomes Roman, Christian, changes name to Jesus...

Horus Romanised, with military cloak and cuirass.

Gods go into the mix

Apis, was the god of Memphis.

A bull was chosen for the distinctive marks on its body and was considered to have been born by a virgin cow impregnated by the local creator god Ptah.

The local trinity was Ptah-Sokar-Osiris.

Apis

Osiris

Osiris was a major Egyptian deity and king of the Underworld.

He began his long career as a god of agriculture and nature during the 5th dynasty (2465 - 2323 BC).

Dionysus

Greek god of agriculture and wine

The Greek god Hermes, showing Eastern influences (Petra).

Trajan's road from Aqaba brought Indian religious ideas as well as spices.

Big Foot

Colossal marble foot from 2nd century Alexandria – possibly from Serapis (British Museum)

The "Holy Family"? The Whole Nativity Sequence, Luxor 1700 BC !

Antinous: 'Appeared After Death'...

Obelisk to Antinous (2nd century, Rome), commemorates 'Osiris-Antinous the Just'

The epitaph records that Antinous 'appeared after death in dreams'.

Roman period – 1st - 4th century AD

Cremation Out!

The portraiture affixed to their mummies shows Roman clothes and jewellery but stylistically is Greek.

Egyptian mummy, Roman/Greek corpse.

Faiyum, Egypt (3rd century AD)

Hedging Their Bets

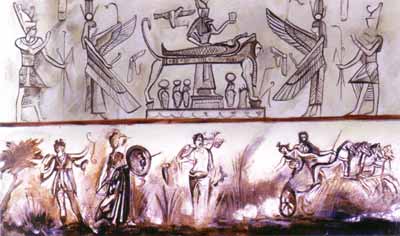

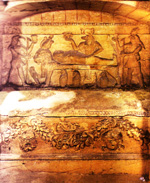

A funereal plaque honouring both Greek and Egyptian myth:

Above, pure pharaonic – Anubis, Isis, Nephthys readying a corpse for the afterlife.

Below, pure Greek – Hades abducts Persephone, Artemis with bow, Athena with lance, Aphrodite

Catacombs of Kom el-Shoqafa (Mound of Shards) 1st century AD.

Sceptic notes the charlatans

Plotinus, the 3rd century Neo-Platonist philosopher travelled throughout Greece, Syria, Egypt and India, observing in particular religious practices. He recorded how readily the myriad priests drifted into fraud, faked 'miracles' and amendments of the truth.

At first glance, the Egyptian pantheon presents a bewildering array of gods having little in common with the Christian godman. But properly understood many Egyptian deities were city or regional "variations on a theme", gods whose fortunes rose or fell with the outcome of human power struggles and dynastic change. Triumphant priests merged useful aspects of a fallen rival's deity with their own favoured god. This process of absorption, assimilation and adaptation continued throughout the Greek, Roman – and Christian eras. Though the basic Christ legend was formulated by apostate Jews, with their expectations of a conquering messiah, and pagan converts, with their fables of dying/reborn sun gods, Egypt provided Christianity with ideas NOT found in the Old Testament: immortality of the soul; judgment of the dead; reward and punishment; a triune god. The ancient religion of Egypt infused the nascent faith of Christ with much of its creed.

Conjuring up Christianity Following the breakup of the empire of Alexander the Great, his general Ptolemy (323-282 BC) took possession of Egypt, Palestine and Cyprus. Alexandria, his capital, built on a spit of land unaffected by Nile floods between Lake Mareotis and the Mediterranean, traded the wealth of Egypt with the Greek world to the north and east. The great port became the hub of commerce between Europe, Asia, India and beyond. Settlers arrived from more ancient Greek cities, bringing Hellenic culture with them. Ptolemy himself encouraged artists and scholars from all nations to continue their work in his cosmopolitan city and, with royal patronage, Alexandria became the intellectual capital of the ancient world. A new syncretic culture emerged. Along with the trade goods into Alexandria flowed every philosophy and creed known in that part of the world. Into this most cosmopolitan of cities religions mingled and mixed and borrowed freely from the ancient faith of Egypt itself. Accessible even today, the catacombs of Alexandria graphically illustrate the cultural fusion of the Roman era – Greek sarcophagi, guarded by Egyptian gods, in Roman military uniform!

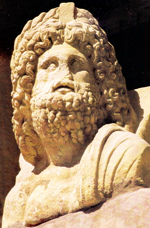

A Syncretic Tradition The Greeks create a universal God: The Greek general Ptolemy styled himself as an Egyptian pharaoh and took the title "Soter" ("Saviour"). As the astute ruler he understood the political value of an official religion. A single, composite deity, one god, one all-embracing system of belief, might unify the diverse, often antagonistic peoples of his polyglot empire and strengthen their devotion to the god's earthly representative – himself. The first Greek pharaoh wanted a single, composite god to bring together his diverse subjects. In a 'classic' example of the process of syncretism, the character and characteristics of several earlier gods were rolled into one, the god Serapis. Of all the Pharaonic–Greek gods Serapis survived the longest, well into the Roman period. In fusing the character of so many earlier gods into Serapis the practice of virtual monotheism was established in Alexandria over several hundred years. The new god embodied aspects of many earlier deities, including the Egyptian Osiris and Apis and the Greek Dionysus and Hades, the Greek god of the Underworld. The Ptolemies intended that the new god should have universal appeal in an increasingly cosmopolitan country. In consequence, Serapis had more than 200 localised names, including (according to correspondence of Emperor Hadrian) Christ! In the 3rd century BC, the worship of Serapis became a State sponsored cult throughout Egypt. With the Roman conquest, the cult spread throughout the Empire. Such a god, to enjoy universal acceptance and devotion, would necessarily possess all the powers and aspects of earlier ones. To create that grand synthesis – in a process that anticipated the actions of the Roman Emperor Constantine several centuries later – Ptolemy put all the resources of the state behind the promotion and sponsorship of an official cult. Major temples of the god were built at Alexandria and Memphis. The Serapeum in Alexandria itself blended Egyptian gigantism with the grace and beauty of Hellenic style. The Serapeum grew into a vast complex, one of the grandest monuments of pagan civilization.

A syncretic funereal tradition Syncretism – The Greeks of Egypt Go Native From the reign of the first Ptolemy in the 4th century BC the Greeks planted Hellenic culture in Egypt. But far from Hellenizing this ancient land, to a great extent the Greeks were Egyptianized by the conquered. This process accelerated after the Roman takeover when the Greeks lost their dominant position.

Out of Egypt

This process occurred most energetically in Egypt, a land awash with religious iconography. From the 3rd century AD onwards, Egyptian Christian – 'Coptic' – art displayed a syncretistic and fused tradition – Roman, Greek and Pharaonic – with a Christian veneer. Such art faithfully reflected a deeper truth: the regurgitation of ancient religious belief in the new guise of 'Christianity.'

Trinity and Saviour God

Regurgitated fables, reused symbols, recycled sacred space

Roman Egypt: Ancient Melting Pot With Rome's annexation of Egypt in 30 BC, the Greeks lost their position as a the country's ruling elite. Now bureaucrats but not rulers, increasingly the Greeks adopted the mores of the native Egyptians. The Egyptian Greeks, who traditionally had believed in immortality only of the soul, abandon cremation and adopted Egyptian mummification – in the optimistic belief in a resurrection of the body, a notion that fed into early Christianity. The Egyptians, always at the bottom of the social hierarchy, were taxed even more by the Romans than by the Greeks. Worse yet, with the whole country reduced to the personal fiefdom of an absentee landlord called 'caesar', they were bereft of their pharaonic god-king. Deeply religious, they were forced into a religious revisionism to find a new godhead for their ancient 'theology'. In reaction (perhaps, resistance) to the Romans, traditional religious interpretations became more 'democratised.'

Among all these displaced and disorientated races moved the agents of diverse cults and 'mystery religions', competing for membership and stealing each others ideas. The most successful cult of all – the supreme example of syncretism – was Christianity.

Pax Romana Coptic 'tradition' has it that Jesus spent his childhood in Egypt – and that the 'Nativity' occurred in the Fayum at Ahnas (Heracleopolis Magna), which just happens to have been a cult centre for Arsaphes, son of Isis! The 'Flight to Egypt' in Matthew, was probably written into the story by the Church of Alexandria – it appears in none of the other gospels and contradicts the return to Nazareth. The Palestinian fantasy of a Jesus Christ was endemic in the religious milieu of Egypt when Constantine gave the Faith its seal of approval. In the hands of 4th century bishop Athanasius, the key aspect of the Egyptian god/human interface – "Begotten, not made, of one essence with the Father" – entered Christian theology. Athanasius wrote:

And the Christians Destroy A God ...

Sources:

Copyright © 2004

by Kenneth Humphreys.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||