Aelia Capitolina – City of the Evangelists!

In print, must be true

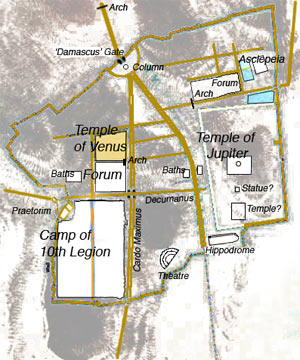

For two hundred years, the municipality of Aelia – the erstwhile city of Jerusalem – was demonstrably and triumphantly pagan, enjoying all the refinements of a Roman colonia. It was also a garrison city for legio X Fretensis – the Roman legion which had destroyed Gamala, Qumran and Masada. In the siege of Jerusalem in 70 AD the Tenth had camped on the Mount of Olives, and rained ballistae onto the city. In the war of 135 it had reduced the fortress of Betar, killing the messianic claimant and the last of his supporters. Post-war, legio decima was heavily involved in reconstruction, its expertise deployed in a vast number of public works.

This pagan past is dimly perceived today, even though the Roman imprint determined the size and layout of the city for more than a thousand years. “Pagan Jerusalem” is regarded by all and sundry as an alien interlude in an essentially Judeo-Christian story. Yet Aelia Capitolina is crucial in the history of Christianity. It was while Jupiter was venerated on “Temple Mount” and Venus honoured in the heart of the city that the fable of Jesus was given form and substance. It was upon, not the city of Herod, but the 2nd century city of Hadrian that the gospellers imposed their fable.

A Roman Colonia

Roman Jerusalem – Aelia Capitolina

Jesus in the city of Hadrian?

“And Jesus answering said unto him, Seest thou these great buildings? there shall not be left one stone upon another, that shall not be thrown down.” – Mark 13.2.

“Now the first day of the feast of unleavened bread the disciples came to Jesus, saying unto him, Where wilt thou that we prepare for thee to eat the passover? And he said, Go into the city to such a man, and say unto him, The Master saith, My time is at hand; I will keep the passover at thy house with my disciples. And the disciples did as Jesus had appointed them; and they made ready the passover.” – Matthew 26.17,19.

To this breathlessly vague direction Luke and Mark add a curious astrological element: the disciples are led to the guesthouse by “a man bearing a pitcher of water” (Luke 22.10; Mark 14.13) – a symbolism typical of Aquarius. Whatever else that suggests (perhaps it’s an oblique reference to John the Baptist, the water man “who goes before”), it has no credibility as history. Who are these men? If Jesus can manipulate their behaviour why not simply “guide” his disciples? Better yet, why not just tell them the address? (And a late booking on the eve of Passover for a party of thirteen? Fat chance!) The whole pericope is a patent literary device, a preamble introducing the last supper itself and the grand finale.

The Praetorium

– Josephus, War of the Jews, 2.14.

"Behold the anachronism!"

“Ecce Homo” – a favourite scene in the Christian dreamscape.

“ Pilate entered into the judgment hall again, and called Jesus, and said unto him, Art thou the King of the Jews? … Then came Jesus forth, wearing the crown of thorns, and the purple robe.

And Pilate saith unto them, Behold the man! … And went again into the judgment hall, and saith unto Jesus, Whence art thou? But Jesus gave him no answer.“

– John 18.28-19.9.

Jesus was here? No chance.

– P. Benoit, Jerusalem Revealed, p 87/88.

Across town, on the eastern side of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre and beneath the Greek Orthodox Convent of St. Abraham, is another, similar cistern – below Hadrian’s west forum.

"Fortress Antonia"

Conventional wisdom – and quite a few models! – locate the Antonia on the site of the present El Omariya madrasa on the northwest corner of the esplanade but that location – on a hill of five metres – does not match the 25 metre hill described by Josephus, nor the vastness of the “tower”:

If Josephus can be relied upon, this vast “multi-city palace”, accommodating camps and an entire legion, cannot be the same “tower Antonia” thrown down by Titus in a matter of days during the siege of 70 AD.

“Caesar gave orders that they should now demolish the entire city and temple, but should leave as many of the towers standing as were of the greatest eminency; that is, Phasaelus, and Hippicus, and Mariamne; and so much of the wall as enclosed the city on the west side. This wall was spared, in order to afford a camp for such as were to lie in garrison.” – War, 7.1.1.

In any event, the Roman garrison, several thousand strong, provided rich opportunities for the enterprising. It is not unreasonable to suppose that, in the middle decades of the 2nd century, some Jews professed Christian beliefs in order to reoccupy businesses and premises left derelict for more than half a century.

A new god in residence – and the "wall of Jesus"

The temenos wall of the temple precinct

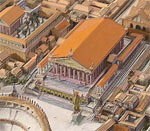

Capitolium temple, Dougga, Tunisia.

A fine example of how a Roman temple was typically placed within a vast sacred space.

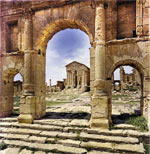

Hadrian’s Arch, Sufetula (Sbeïtla) Tunisia.

How the temple of Venus in Aelia may have appeared viewed through the monumental arch on the west forum. The Church of the Holy Sepulchre now occupies the site.

Temple of Venus and Rome, Rome.

Close by the Colosseum, Hadrian built a dual temple – the largest in Rome in fact. It was no doubt a prototype for the structure in Aelia. Today, its ruins, though large, can easily be missed.

Show time!

- Robert Gordon, Holy Land, Holy City (Paternoster, 2004)

- H. J. Richards, Pilgrim to the Holy Land (McCrimmons,1985)

- S. Gibson, J. Taylor, Beneath the Church of the Holy Sepulchre (Palestine Exploration Fund, 1994)

- Joan Taylor, Christians and Holy Places: The Myth of Jewish-Christian Origins (Clarendon, 1993)

- Martin Biddle, The Tomb of Christ (Sutton, 1999)

- Jerome Murphy-O’Connor, The Holy Land (Oxford, 1986)

- Karen Armstrong, A History of Jerusalem (HarperCollins, 1997)

- Jerusalem Revealed (Israel Exploration Society, 1975)

- Sami Awwd, The Holy Land (Sami Awwad, 1993)

- Peter Walker, In the Steps of Jesus (Lion Hudson, 2006)

"A Second War with Rome

The Emperor Hadrian (117-138) – Publius Aelius Traianus Hadrianus.

Mark of the Legion

Mass production, Roman-style

Porta Neapolitana

A semi-circular plaza

Cardo Maximus

Cardo Maximus at Apamea, Syria

Hadrian's other temple to Venus.

The torso of a statue from the Temple of Jupiter which stood on Temple Mount.