Egyptian Roots of Catholicism

Relics, Demons, Miracles

“Meaningful and eloquent myths and philosophic formulations … became in their turn garbled traditions, reused by later and lesser authors.”

James Robinson, The Nag Hammadi Library, p2.

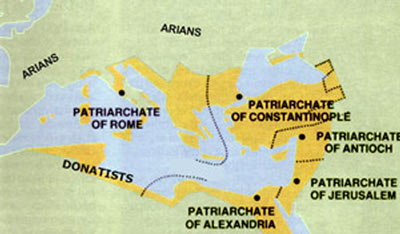

Nestorius and his 'Mother'

With gifts of gold to the imperial coffers, the alliance of Alexandria and Rome hounded Nestorius out of office. Greek influence in Rome waned as Egyptian ideas flourished.

Regurgitated fables, reused symbols, recycled sacred space

Originated in Egypt, copied in Rome

Monasticism

Holy tableaux… pioneered in Egypt, copied in Rome.

The Double Whammy – 'Two Christs in One'

Where Did They Get Their Ideas From?

The ankh imparts the breath of life ("resurrection") to a dead pharaoh

Winged sun cross – (Nimrud, Iraq, c. 850 BC)

Sun cross (swastika) – ancient symbol of good fortune.

Greek Cross. The first appearance of a cross in Christian art is on a Vatican sarcophagus from the mid-5th Century.

Buddhist swastika cross

Irish 5th century grave stone, Aglish, County Kerry (note swastikas).

The ankh cross was associated with Maat, the Goddess of Truth. It also represents the sexual union of Isis and Osiris.

The ubiquitous ankh (a symbol of life) remained in use throughout the Pharaonic period.

Ankh on Coptic tapestry (5th century AD. British Museum)

Coptic Cross. In the 3rd/ 4th centuries the ankh was absorbed into Egyptian Christianity (where it was known as the 'crux ansata' – the 'eyed' or 'handled' cross)

Latin Cross ('crux immissa') The Coptic ankh was adopted in Rome during the 4th/ 5th centuries and simplified into the familiar crucifix.

In this form it echoed the ancient scarecrow, a human effigy used to encourage crop fertility.

Sources:

- William Dalrymple, From the Holy Mountain (Flamingo, 1998)

- Michael Walsh, A Dictionary of Devotions (Burns & Oates, 1993)

- Dom Robert Le Gall, Symbols of Catholicism (Editions Assouline, 1997)

- Leslie Houlden (Ed.), Judaism & Christianity (Routledge, 1988)

- Norman Cantor, The Sacred Chain – A History of the Jews (Harper Collins, 1994)

- R. E. Witt, Isis in the Ancient World (John Hopkins UP, 1971)

- Alison Roberts, Hathor Rising-The Serpent Power of Ancient Egypt (Northgate, 1995)

- Timothy Ware, The Orthodox Church (Penguin, 1993)

- Robert Bauval, Graham Hancock, Keeper of Genesis (Heinemann, 1996)

Related Articles:-

Crackers? No, its really Jesus

But it doesn't end there:

Monasteries rivaled the towns (St Catherine's)

Pharaoh?

Pope?

Pope?

Pharaoh?

Thotmosis I keeps hold of his ankhs

6th century Coptic Cross