Sex and Primitive Christianity

The sociopathic Christ cult adjusts its dogma for worldly advantage

– a Compromise with Reality

As the 2nd and 3rd centuries passed and it became only too obvious that there would be no imminent return of the godman, the church and its theorists had to adjust to the reality – and opportunity – of an institutional church and a human race that would perpetuate itself whatever madness the theologians urged.

Following the example of the Jewish priests, who collected all manner of “offerings” for unclean sexual practices, the henchmen of Christ would regulate, exploit and license human sexuality on a truly monumental scale.

Sexual mores of the Romans

Natural, Normal and Exotic

“For it is the semen, when possessed of vitality, which makes us men.”

– Aretaeus of Cappadocia, Greek physician, 1st century AD. (Quoted by Brown, p10)

In matters carnal, the Roman world of the imperial age was unblighted by either “shame” or “guilt”. Before the triumph of Constantine and his church, the sex act had no notion of “sinfulness” and the sight of human genitalia did not offend. Copulation and the erect penis were subjects suitable for public display and private art. The phallus was a ubiquitous “good luck” charm, worn by many, etched on fine glass, emblazoned on shop hoardings, adding beauty to garden ornaments or directing travellers on road signs. Sexual imagery often had ironic or humourous purpose rather than erotic. For a triumph, the Emperor Domitian minted coinage showing an undraped figure, Germania captive.

In all things, the Roman public had an appetite for the spectacular and the exotic. The theatre, aside from the entertainments of comedy, tragedy and farce, featured a wide variety of eroticism, including naked acrobats and burlesque shows in which the sex act was either mimed or performed. The 1st century poet Martial records bestiality performed as public entertainment (Spectacula 5). In taverns, waitresses might provide sexual services for customers. Suetonius noted that nude girls served at banquets (Life of Tiberius 42.2). A late Roman (and Christian!) emperor, Justinian, even married a performer from the circus famous for her erotic buffoonery and made her empress.

Yet “fertility” had an official, and pragmatic purpose: promotion of the family. The empire was always in need of manpower. For all its civilisation, life expectancy in the Roman world was not great. Female death in childbearing was a common fate. An expansive empire needed its colonists. Society expected its citizens to expend their sexual energies in begetting and rearing children. Even the Vestal Virgins were free to marry later in life, their chastity in no sense an exemplar for society as a whole.

Marriage was encouraged. Widows and widowers remarried. They did not yet retreat into “piety” or perpetual mourning nor lavish the family legacy on the Church. Augustan laws penalized bachelors and rewarded families. Young girls early in life were utilised as baby factories; the median age for marriage may have been as low as 14.

“As the opponents of Paul and Thecla pointed out, procreation, and not the chilling doctrine introduced by Saint Paul, was the only way to ensure a “resurrection of the dead.” The true resurrection was … that which takes place through the nature of the human body itself … the succession of children born from us, by which the image of those who begot them is renewed in their offspring, so that it seems as if those who have passed away a long time ago still move again among the living, as if risen from the dead.”

– Brown, The Body and Society, p7.

Only religious fanatics, convinced that the dead would rise and the world would end, could see virtue in mass chastity. Unfortunately, those fanatics would capture control of the empire.

Sexual mores of the Romans

“To be carnally minded is death; but to be spiritually minded is life … The carnal mind is enmity against God … They that are in the flesh cannot please God … If you live after the flesh, you shall die: but if you through the Spirit do mortify the deeds of the body, you shall live.”

– Romans 8.6,13

“The chaste severity of the fathers, in whatever related to the commune of the two sexes, flowed from the same principle; their abhorrence of every enjoyment, which might gratify the sensual, and degrade the spiritual, nature of man.”

– Gibbon, Decline and fall, 15.

In the first century of its incarnation Christianity was a morbid, sociopathic death cult, unnoticed by most of the Roman world. Convinced that they alone would survive the impending apocalypse, the Christians went about their affairs in daily anticipation and fear of their Lord, the saviour who would descend from the clouds in glory to judge the quick and the dead. Nothing in the demeanour, dress or word of the saints could be allowed to jeopardise imminent judgement and the hoped for salvation. In a manner reprised time and again in the centuries ahead by puritans and fanatics, abstinence, chastity and somber domestic virtues, laced with a bitter spite towards the vast herd of unbelieving humanity, distinguished the Christians from their insouciant neighbours.

But time passed, the Lord did not come, and the first generation of the brethren “fell asleep”. To replace the dead, marriage, solely for the purpose of procreation, became tolerable, at least within the faith. But the marriage bonds came with the caveat of indissolubility. They would last for the eternal age yet to come and a remarriage was nothing less than adultery.

Like every subsequent apocalyptic cult that has boldly proclaimed the End Time and embarrassingly survived into a new era, Catholicism adroitly adjusted its doctrine for the “long haul”.

Catholicism – a compromise with reality

How could the early evangelists of Christianity compete with the taverns, the circuses, the theatres, the baths and the bordellos that graced every Roman city? Only with difficulty, only by exploiting the misfortunes that befell the Roman world and only by appealling to neglected marginal elements (“matrons and orphans”) of the population (even slaves could attend the games).

Catholicism was an opportunistic compromise in the face of need and opportunity for a universal faith. Within two or three generations it outgrew its early austere fanaticism (refusal to serve in the legions, will to martyrdom). Fanatics like Tertullian left to join marginal sects of purists, leaving more urbane Catholic bishops to frequent the corridors of the imperial palaces.

Orthodoxy borrowed without embarrassment or apology from its enemies and in particular drew from the books of gnostic heresy. “Pleasures of the flesh” remained an enemy, just as surely as the fertility gods and goddesses of the pagans who delighted in procreation. But now a taste of power favoured accommodation and rapprochement with a disbelieving world.

In an age when Judgement Day and the Kingdom of Heaven had been anticipated at any moment, celibacy and denial of the body had a passable rationale. The world was about to end. But as the Apocalypse retreated further and further beyond the horizon, few could succumb to Christianity’s austere, joyless dictates without penalty. Those who did, reclusive hermits, anchorites, stylites and the rest of the menagerie, were lionized by a more worldly church. Admired and applauded for their “heroic piety” and useful as propaganda for the faith, they were contained within a more pragmatic and universal Church.

A triumphant Catholicism would forgive “pleasures of the flesh”. After all, huge profits were to be derived from venial sin.

A celibate priesthood?

From the very foundation of the Church, “sins of the clergy” permeated the organisation from top to bottom.

Before the patronage of the Roman state filled the coffers of the Church, rich Roman matrons paid the bills, fed the priests and made their great houses over as meeting places for the brethren. The priest, as a respected and powerful figure, was often left alone with a cheerless widow or a vulnerable novice. He became privy to the most intimate confidences and indiscretions. The temptations, both venal and carnal, were many. His position was most privileged. Who but a churchman could visit a woman in her home while her husband was away? Who could question the calling of lay women into the presbyteries of the clergy – or doubt the wisdom of entrusting minors into their care? Pagan critics often questioned the purported purity of the saints. Even the epistle of James had a cryptic warning, cautioning the brethren when visiting widows and orphans to keep their “hands off”:

Pure religion and undefiled before God and the Father is this: to visit the fatherless and widows in their affliction, and to keep himself unspotted from the world.”

– James, 1.27.

The Church hierarchy guarded jealously the wealth that was passing into its hands. But the hierarchy had no intention of allowing power to pass back to its female benefactors, no matter how influential or necessary they were, nor would it brook any priest forsaking his holy calling and marrying into that wealth.

Catholicism met the challenge in a characteristically simple and pragmatic way. It instituted a prerogative, exclusive to male priests, of “laying on hands” and conducting the rituals of the Eucharist. It was the beginning of an avowedly patriarchal church and ever-widening gulf between the clergy and the laity. Had not Jesus himself called only men to be his disciples?

The device effectively sanctified the exclusion of women. They could be helpers but never protagonists. In later centuries they would be regimented into approved “orders”. Among the first of such “orders”, were collectives of Christian widows, welcomed by a male clergy for their “charity” but denied any leading role. It was a smart move, one that gave Catholicism an edge over both rabbinic Judaism and gnosticism – the former rejecting women and the latter rejecting wealth.

“The orthodox could accept such wealth with a clear conscience. The slow rise of the Christianity of the great Church at the expense of the more radical groups was made possible by that elementary decision.”

– Brown, The Body and Society, p144.

In the matter of sexual procuring, the Church was more accommodating. It was not unsympathetic to the physical needs of its henchmen, rather the reverse. It required not sexual continence but merely celibacy. A priest could acquire a concubine – or several – and there could arise no claims from wives or offspring to lands and property coveted by the church. Priests were at liberty to live as libertines, far beyond the excesses of the pagans.

After all, rape and debauchery were as nothing compared to the mortal sin of denying Christ. Now that deserved execution.

The Church of God

The triumph of Constantine and the subsequent state patronage of Christianity opened up vast new opportunities for sexual predators. In the mind of the superstitious emperor the priesthood were beyond the reproach even of his own grandiose power.

” Constantine … said that it was not permissible for him, as a man, and one who was subject to the judgment of priests, to examine cases, touching gods, who cannot be judged save by God alone. Petitions containing accusations against priests … he put into the fire without even looking at them, fearing to give publicity to accusations and censures against the fathers .. Wherefore he said,

‘Verily if with mine own eyes I had seen a priest of God, or any of those who wear the monastic garb, sinning, I would spread my cloak and hide him, that he might not be seen of any.’ “

– John of Salisbury, Policraticus, 4. 3.

Ecclesiastics were raised beyond mortal law, with the result that clerical celibacy, so-called, brought great immorality in its train. Not just the fleecing of pious matrons but teenage mistresses, incest, prostitution and perversion ever after would be the mark of the Church triumphant. The young, the old, male and female, the naive and the headstrong, all were at risk. Sexual corruption became a systemic and endemic feature of Holy Mother Church. Then as now, wrongdoers were seldom punished – scandal was bad for morale.

The so-called “Apostolic Constitution” of the early 4th century – rules and regulations for the clergy – required unmarried ministers to remain celibate but allowed priests already married to keep their wives. No doubt the double standard set up tensions within the ranks. Then in 366, Pope Damasus set an example by abandoning his own wife. The boss of bosses knew what he was doing:

“A celibate priest owed total allegiance not to wife and children but to the institution. He was the creature of the institution. The Roman system was absolutist and hierarchical. For such a system to work, it needed operatives completely at the beck and call of superiors … The papal system would collapse without the unqualified allegiance of the clergy; celibacy alone could guarantee that sort of allegiance.”

– De Rosa, Vicars of Christ, p420.

The philandering Damasus, known as the “matronarum auriscalpius” (“ladies’ ear-tickler”), actually ran Rome’s city brothels, heavily patronised by the clergy and visiting pilgrims.

The pressure to “unwed” clergy went on for generations. Twenty years after Damasus, Pope Siricius actually forbade priests who remained married from sleeping in the same bed as their wives. Following the Second Council of Tours (567), a priest who broke this rule could be excommunicated for a year and his wife would receive a hundred lashes. And yet it remained commonplace for Catholic priests to have multiple “wives” and mistresses. Pope Gregory II in a decretal in 726 ruled that “when a man has a sick wife who cannot discharge the marital function, he may take a second one, provided he looks after the first one” (De Rosa, p349), Married clergy were to be found in the Church until the Second Lateran Council of 1139, when Pope Innocent II, annulling the decisions and ordinations of “anti-pope” Anacletus II, voided all marriages of priests.

The “reformer” Innocent was the very same pope who confirmed the condemnation of French philosopher and scholar Peter Abelard (castrated and confined to a monastery).

The pimping clergy

The Christian clergy, more than all others, have inveighed against “lust”, held to be a mortal sin which jeopardizes the eternal soul. Yet in practice the hierarchs of the church have indulged in every carnal vice and then confounded their licentiousness with cupidity and violence. But this is not merely the fallibility of human nature transgressing God’s perfect laws. The twisted and inhuman precepts of Christianity, which masquerade as “love” sublime, are perverted in design as well as criminal in consequence.

The “sex crimes” inherited from Judaism became rank nonsense in the musings of the Church fathers. In time, the Church would extend its rules on “blood marriages” (consanguinity) out to a ludicrous seven generations, but not because of any concern for in-breeding. In a pre-industrial village almost everyone could be shown to have had a common ancestor. The real intent was to collect fees for dispensations to marry which were levied on almost anyone who had extractable wealth. Pimp-in-chief was the pope himself. Sixtus IV (1471-1484) not only licensed the brothels of Rome, he taxed priests for their mistresses and even sold permits which allowed rich men “to solace certain matrons in the absence of their husbands” (De Rosa, p101).

True love, the surrender of the individual to another in physical and emotional pleasure, their bonding together into a union stronger than all others, the sacrifice each to the other, ran counter to an unchallenged primacy of the religious cause and an unfettered loyalty to the Church. Natural affection was driven out by “Christian morality”, which, when it did not fill the believer with the terrors of the pit, brought in its train private traumas and public shame. In a million unknown torments across two millennia the psychotic disorder of Christianity wrought havoc and misery. The counterfeit passion on offer, even to claims of earth-moving ecstasy, was a “spiritual communion” with the illusory godman, an audacious claim incompatible with reality, though perhaps real enough in the religious imagination.

To be sure, Christianity had comforters on offer for the lost souls it created, the depressed, the lonely and the frustrated. Whether a flickering candle, or an icon of the virgin, the falsetto voices of a choir, or the pomp and theatricals of the sacraments, the majestic gloom of a basilica or the homely comfort of a Bible study class. It was – and is – a world of sham and subterfuge – and, of course, fellowship with Christ, a placebo conjured from the ether.

The Gospel of Sin

Is Sexuality the nemesis of Spirituality?

Aurelius Augustinus (354-430), Bishop of Hippo (in what is now Algeria), was an early systematizer of Christian theology. He developed a view of original sin which prevails in some quarters even today.

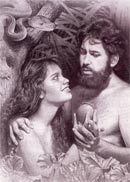

In Augustine’s belief, the sin of Adam and Eve was transmitted, generation by generation, throughout history by the act of intercourse. Thus children are born in sin, the result of a further act of sinning by their parents. This was because sexual urges are demonic in origin and should be resisted by the exercise of freewill. Only procreation justified the act at all, even within marriage, and certainly carnal pleasure should be no part of the process.

Where on earth did Augustine get such monstrous ideas?

Augustine spent his formative years in youthful rebellion against his violent pagan father and up-tight Christian mother, first as a gang member (the Euersores or ‘wreckers’) and then as a Manichaean heretic. He spent nine years as a follower of Mani, a 3rd century Persian mystic who had elaborated a dualistic system of cosmic conflict, of good versus evil. As “matter” was intrinsically evil it freed Augustine for a life of profligacy.

In later life, he would come to regret the heartless behaviour of his youth, and in particular the ambition to marry well which led him to abandon more than one concubine (one the mother of a child that died).

“When that mistress of mine which was wont to be my bedfellow, the hinderer, as it were of my marriage, was plucked away from my side my heart cleaving unto her was broken by this means.” – Confessions.

Guilt (and maternal influence) got the better of Augustine and instead of marriage he found Christian asceticism. Yet he remained tormented by his own “concupiscence” (“when God is utterly forgotten and creatures revel shamelessly in one anther” – Armstrong, p144). This troubled soul hammered out the dysfunctional dogma that would blight the most natural of human proclivities for two millennia.

Viagra moment?

“At times, without intention, the body stirs on its own, insistent. At other times, it leaves a straining lover in the lurch, and while desire sizzles in the imagination, it is frozen in the flesh; so that, strange to say, even when procreation is not at issue, just self-indulgence, desire cannot even rally to desire’s help – the force that normally wrestles against reason’s control is pitted against itself, and an aroused imagination gets no reciprocal arousal from the flesh.”

– Augustine, City of God, 14.17.

Perhaps the venerable saint just couldn’t get it up!

From India, an Alternative View

Sex as the highest expression of the divine!

Tantric Buddhism. The deity Cakra Samvara copulates with his spiritual consort Vajravarahi. The union is emblematic of a perfect combination of wisdom and compassion. (British Museum)

Tãrã – Mahayana Buddhist goddess of serenity, health and good fortune. This firm breasted playmate of the god Avolokitesvara helped him save sentient beings from suffering.

Sources:

- Cullen Murphy, The Word According to Eve (Allen Lane, 1998)

- Richard Dawkins, The God Delusion (Bantam, 2006)

- Sigmund Freud, The Future of an Illusion (1927)

- Sam Harris, The End of Faith (Free Press, 2005)

- Paul Tabori, A Pictorial History of Love (Spring, 1968)

- Elaine Pagels, The Gnostic Gospels (Phoenix, 1980)

- Uta Ranke-Henemann, Eunuchs for the Kingdom of Heaven (Penguin, 1993)

- Peter Brown, The Body and Society (Colombia, 1990)

- P. Aries, A. Bejin, Western Sexuality (Blackwell, 1986)

Related Articles:

"Beware of the Penis"

“Priapus, over-endowed and over-sexed by definition … warded off petty thieves, upon whom, if caught, he would inflict the homosexual punishment.”

– Antonio Varone, Eroticism in Pompeii, p14/5.

Sign of the Happy Penis

“Here dwells happiness” – House of Pansa, Pompeii

Denarius of Domitian, 85 AD. A half-naked Germania.

“Even the reverses of the Greek and Roman coins were frequently of an idolatrous nature. Here indeed the scruples of the Christian were suspended by a stronger passion.”

– Edward Gibbon, Decline and Fall, 15.

Unholy Grail?

On a fine silver cup, a man has sex with a youth.

From the House of Menander, 1st century Pompeii (‘Warren cup’, British Museum).

Randy god becomes heroic Christian martyr

In a curious recycling of ancient piety, Priapus metamorphosed into a noble Christian saint!

Supposedly, the first bishop of Lyons was “Pothinus”, who (in his 90th year, no less) was cruelly martyred by that dastardly Marcus Aurelius, actually the most sublime of Roman emperors.

His death, along with a claimed fifty others, became a cause célèbre of Christian heroics, the “martyrs of Lyons” – though we are indebted to the 4th century propagandist Eusebius as our witness to this doubtful episode.

Pothin’s name in time became Foutin, giving rise to the verb foutre (“to fuck”). Shrines to Saint Foutin sprang up all over the region.

Scrapings from the saint’s wooden phallus were made into a portion, providing a fertility service for women hoping to get pregnant.

(Confession de Sancy, Pierre de L’Estoile)

Christian sex attitudes? "Carnal woman"

Ever a Manichaean?

– Augustine, Soliloquies.

In his major work Civitate Dei (City of God) St Augustine, the first theologian in the west, counterpoised an eternal Christian “spirituality” to a doomed material world.

In his major work Civitate Dei (City of God) St Augustine, the first theologian in the west, counterpoised an eternal Christian “spirituality” to a doomed material world.

Nip and tuck

Christianity did not require circumcision (though it continued among the Coptic Christians of Egypt and Ethiopia) but it did countenance castration (de rigueur in the bureaucracy of Byzantium).

Glorification of chastity

Nuns get none. But they love Jesus.

“The only unnatural sexual behaviour is none at all.” – Freud

As Christianity edged closer to worldly power, chastity replaced charity as the central calling of the faith.

Love demanded

” Jesus said unto him, Thou shalt love the Lord thy God with all thy heart, and with all thy soul, and with all thy mind.

This is the first and greatest commandment.”

– Matthew, 22.38.

Love given

” I do believe in the scripture and am in love with God and that he sent his son to die for me … Having a friend that will never leave me or forsake me is a comfort as I watch this world unfold at the seams.”

– email to JNE, 2nd March 2007.